Mexico was the mother province of the US Claretians until 1922. In the 1880s the Claretians Missionaries in Spain decided that Mexico offered a good challenge, with its “faith as robust as oak trees” but hampered by “poor circumstances for religion.” The Spanish congregation established its first residence in Mexico City in 1887, and gradually took on ministry in Guanajuato, León, Monterrey, Orizaba, Puebla, Toluca, and, in 1902, San Antonio. In Mexican cities they administered parishes, established schools, taught catechism, including a ministry to the deaf in the capital. From these urban foundations the missionaries regularly fanned out into rural Mexico’s ranches, haciendas, mining towns, and indigenous villages. The Claretians crossed the republic in every direction, mostly by train, but often on horseback or wagon on slow and arduous journeys.

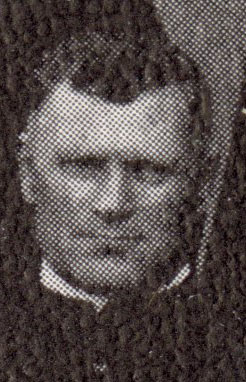

In 1902 Fathers José Rementería and Jerónimo Pomés, both Spanish-born Claretians, took on a Lenten mission at the Hacienda del Lobo. Tucked away in the mountains of Querétaro, the centuries-old estate was home to five thousand inhabitants, many of whom were indigenous people. During their stay, the priests urged people to confess and take communion before Holy Week. After the final night’s sermon, thirty-two-year-old Fr. Rementería dismissed the women and locked the church door. Inside the priest oversaw the chanting of the Miserere: “Tenme piedad, oh Dios, según tu amor, por tu inmensa ternura borra mi delito, lávame a fondo de mi culpa, y de mi pecado purifícame.” The men begged God’s mercy, asking to be cleansed of their sins. The men took off their shirts and whipped their bare backs. Fr. Pomés, age twenty-six, noted with satisfaction as blood darkened the church floor. The flagellants formed a line as they left the hacienda church. As they processed to their modest homes, the men’s mournful songs penetrated the darkness. With that, the missionaries had accomplished the mission’s goal: the entire community at the Hacienda del Lobo had purified their consciences. 4,900 people there had taken communion.

Crowning this accomplishment of Lenten observance, at midnight the Claretians led a pilgrimage to the Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Dolores de Soriano (today a basilica). In orderly fashion, the hacienda’s men and women made their way through the dark, presided by the missionaries, chanting the Rosary and “beautiful verses to Jesus and Mary.” After some twelve miles, the procession arrived before daylight. The people dropped to their knees, entered the sanctuary, sobbing as they humbly processed. Pomés moved by the experience, effused “I couldn’t contain myself—I cried like a child.” Rementería then celebrated Mass: 1,500 faithful took communion. As chronicled by these missionaries, it seems that the Spanish Claretians and the Mexican people found common ground in their Catholic faith and rituals. Frs. Rementería and Pomés may not have known the local devotion to Nuestra Señora de Dolores de Soriano, but themselves pledged to the Immaculate Heart of Mary, Claretians appreciated demonstrations of “robust” faith played out in any Marian devotion. Both Pomés and Rementería would later serve Mexican people in the U.S.

Deborah E. Kanter wrote Chicago Católico: Making Catholic Parishes Mexican (University of Illinois Press, 2020). Her current research focuses on the Claretian Missionaries in the US and the creation of a national Latino ministry.